THE ARTISTIC PROCESS

I’m writing these few words in response to several questions from the public at a recent exhibition in Brussels: Why black and white? How do you reconcile your career as an archaeologist with your artistic creations?

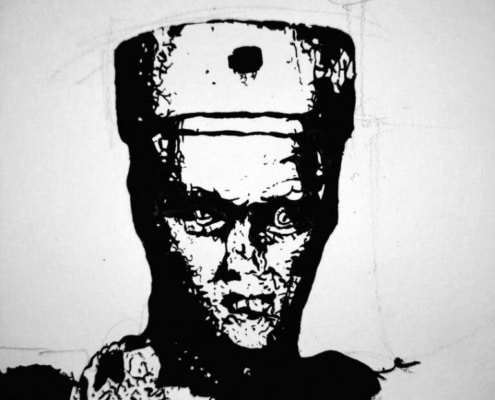

First of all, I love black, not as much as Soulages, but to the point where I only own black T-shirts. When I draw for myself, I like pencil (see my sketch of Antisthenes for example) or watercolour (see my Bartlett head Aphrodite watercolour for example). But when it comes to those large, somewhat provocative drawings that are both historically and aesthetically inspired, I become completely monochrome. However, I prefer to use the term bichrome, as a reminder that black is just as important as white in my drawings. After all, if white is a mixture of colours, black is the absence of them.

I need strong contrasts and sharp lines to tell a story. I would lose myself in the shimmer of colours. I avoid them to refocus, to tell a story as forcefully as possible.

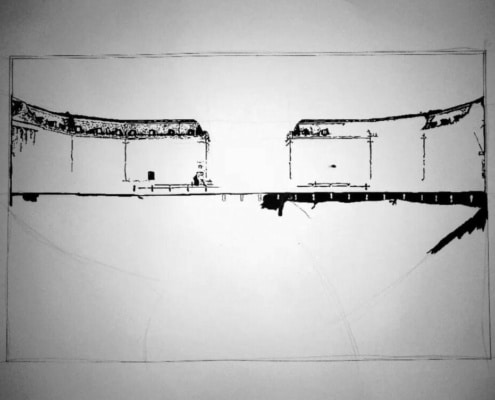

That said, my drawings are painted in black ink, never in white, even in Dante sotto la città. The white areas are those that have not been covered in black. I paint as if in reverse, because I like to reveal the dark side, to dig up the past in a way. I try to give the viewer the pleasure of being an archaeologist as they examine my drawings.

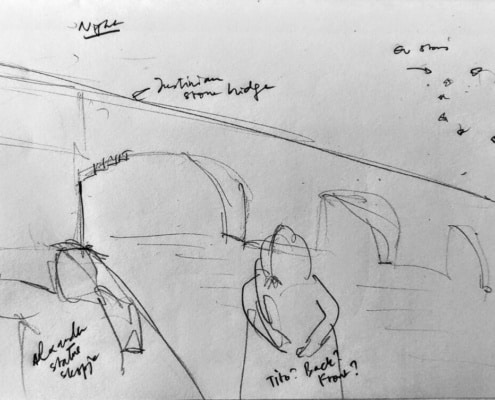

Each drawing is the result of a very long process that can last months, made up of research, reading that can sometimes seem endless, books, websites, scientific articles, numerous sketches, sometimes short study trips, visits to museum collections that are sometimes inaccessible to the public. All this informs the drawing and the text that always accompanies each drawing.

I must stress that I am in no way setting myself up as a universalist or a ‘specialist in everything’, far from it. Yet, I am very curious and I have all the well-honed reflexes of a researcher. I know where to find and quickly assimilate the information I need, or who to ask for it if necessary. My drawings are also inspired by wonderful encounters and discussions with colleagues here in Europe or elsewhere. Without the guided tour of one of the curators of the archaeological museum in Venice and the long discussion with the spolia specialist, my drawing Brotherly Love simply would not have seen the light of day. They showed me the hidden side of Venice in a way that only Venetian historians and archaeologists could.

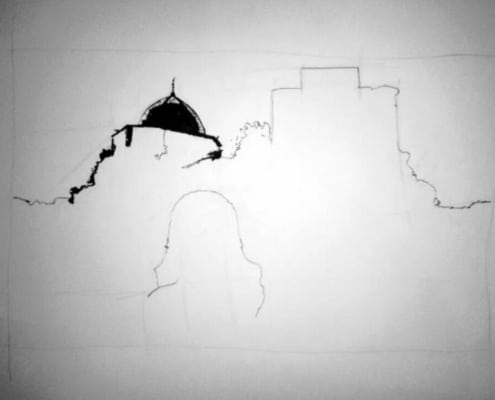

During this research, but especially afterwards, I usually sketch a lot, usually in HB pencil (which, depending on the pressure applied and the angle, allows a wide range of tones) in notebooks that I fill with objects or buildings that interest me.

Often it’s the ideas that feed into the image, but sometimes it’s an image that imposes itself on my mind and from which I can’t tear myself away, a vision so strong that the ideas scroll by like shadow puppets.

Composition takes up an infinite amount of my time, because my visual memory, which has been highly developed by archaeology (after all, for my doctorate between 1999 and 2002 I analysed nearly 130,000 Greek vases and redesigned several hundred, see Greek Vase Painting and the Origins of Visual humour, Cambridge University Press, 2009, 2012, 2014), puts the brakes on my artistic impulses.

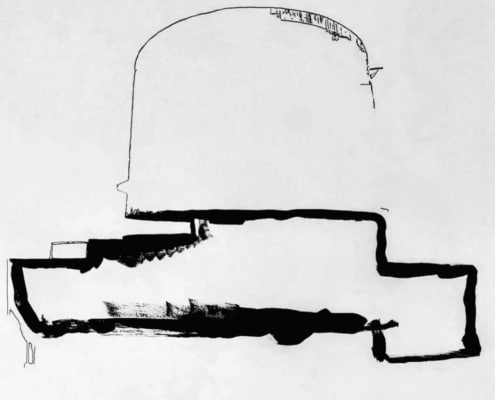

When I talk about composition, I’m referring to the search for pure lines and simplified geometric elements such as squares, cubes, spheres and triangles, which I arrange in all directions until I’m satisfied with the movements of the drawing.

Sometimes I want an element to emerge from a raging sea, as in The Vanished, or for the flowing blood of the Cinquantenaire to create a puddle in the shape of the Congo in The Devourer of Lives, or sometimes I have to deal with the difficulty of simultaneously showing the nuclear mushroom and the blast of the bomb in the Hiroshima drawing. I imagined that the river flowing through Hiroshima would be transformed into a giant Hokusai-style wave that moves away from the impact of the bomb and carries the Yokai away from the Atom. This drawing is the direct result of an overall vision of the drawing that came to mind one night, a kind of nightmare vision.

Using the grey of the pencil, I imagine the chiaroscuro effects, I test, I try to see if white will prevail or black depending on the meaning or content of the drawing. Sometimes the meaning comes first, sometimes the aesthetic need.

I cheat, I twist, I have fun reshaping objects to suit my aesthetic vision and the meaning of the image. I light up the Palazzo Ca’ da Mosto on the Grand Canal in the middle of the night in Brotherly Love, because that’s what interests me, its typically Byzantine style; in the same drawing, I transform the high relief of the Tetrarchs, which is actually a group of four figures, embedded in a corner of St Mark’s Basilica in Venice. I turned it into a pair of brothers in the round, embracing each other and flowing into the canal. Sometimes I make the distinctive features of a character I’m illustrating disappear, like the famous long beard of King Leopold II in The Devourer of lives, or I twist and transform the shape of the nuclear mushroom in Hiroshima, so that it takes up a huge space in the drawing, as in my vision from which the drawing comes.

Then there are the sketches of the final drawing, well before I start work. As the final drawing is done in Indian ink (with brushes of various sizes made of sable hair and with a pen, Tachikawa Nib Maru Pen T77 Soft), I know that the drawing will be slow because with Indian ink, there is little room for error. The ink is indelible. I use several Indian inks. One day I hope to get some Sumi Kobaien ink sticks from Nara in Japan. We’ll see. I’ve tested many types of paper, and I really like Canson 224g, which is dense enough to carry large flat black areas.

Since I’ve been working with the talented lithographer Bruno Robbe, on some drawings the contrasts are even more accentuated and that works very well.

In conclusion, although my art is a little dark, it is not sinister: I try to unearth a past that is often disturbing and has become invisible, to help conjure up memories.