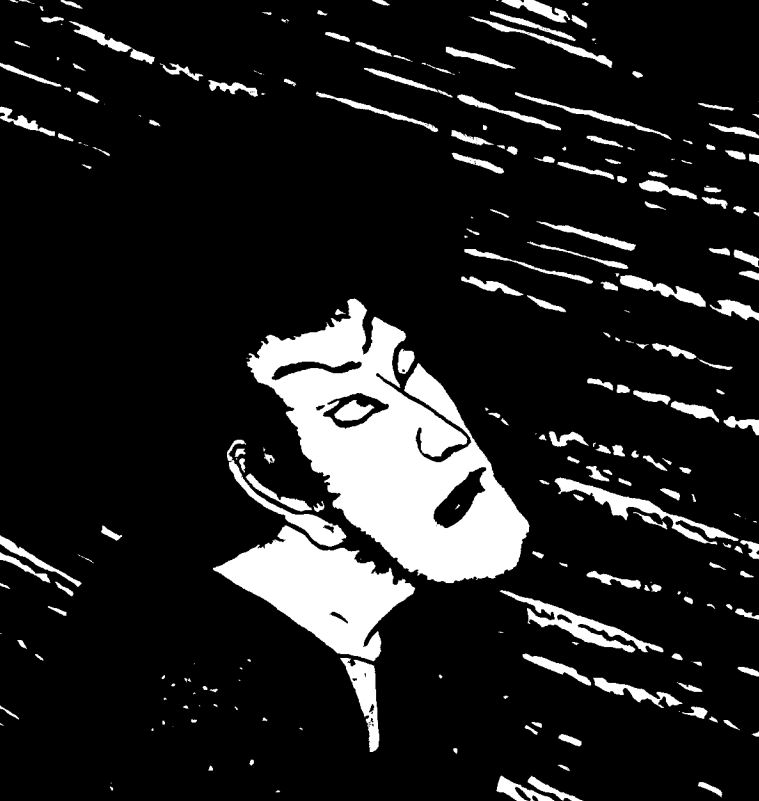

“Hiroshima”, Alexandre Mitchell, 2023 (50 x 65 cm, encre de Chine)

Le 6 août 1945, l’humanité est entrée dans l’ère atomique. Rien dans l’histoire n’est comparable à cette démonstration stupéfiante de puissance destructrice et aux pertes humaines en si peu de temps. La puissance de l’explosion a été estimée à 15 000 tonnes de TNT. Un seul kilogramme de TNT peut détruire une voiture. La bombe représentait 15 millions de kilos de TNT. Quelques minutes après l’explosion, presque tous les habitants situés à moins d’un kilomètre du point zéro étaient morts, presque toutes les structures situées à moins de deux kilomètres avaient été détruites et les vitres d’immeubles avaient volé en éclats à une vingtaine de kilomètres de là. Entre la vague d’explosion initiale, la vague thermique qui provoqua l’embrasement d’oiseaux en plein vol et l’autocombustion de papier à 2 km du point d’impact, la tempête de feu qui ravagea la ville et, plus tard, la radioactivité et les cancers qui en découlent, le nombre de morts à Hiroshima dépassa probablement les 150 000 individus.

La bombe larguée trois jours plus tard sur Nagasaki avait une puissance destructrice supérieure de 40 % à la première.

Dans l’Antiquité, l’exemple ultime d’une destruction causée par l’homme est la prise de Carthage par les Romains en 146 avant notre ère. Après plusieurs guerres sanglantes au cri de « Delenda est Carthago« , la République romaine vainquit finalement son seul adversaire dans la région méditerranéenne et l’image de son anéantissement traversa les siècles. À tel point que certains allèrent jusqu’à dire que les Romains avaient labouré la ville et y avaient versé du sel, car ils souhaitaient que rien n’y pousse plus jamais. La destruction succéda à une victoire longtemps recherchée. Pourtant, dans le cas d’Hiroshima et de Nagasaki, la destruction n’était pas punitive, c’était une menace. Elles précédèrent la capitulation japonaise et la victoire des alliés.

Ceci peut expliquer, au-delà de la capitulation du Japon, l’incroyable choix de cette nation de renoncer à des siècles de tradition militaire pour embrasser une identité non violente. Elle l’a fait avec le même sens de l’honneur, le même dévouement et la même recherche de la perfection. L’émergence d’une nouvelle identité pacifiste a conduit le Japon à devenir, par la suite, un médiateur de la paix au niveau mondial.

Le « dôme de la bombe A », la seule structure restée debout près du site du bombardement atomique d’Hiroshima, est aujourd’hui classé au patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO et fait partie du parc du mémorial de la paix d’Hiroshima. Son armature métallique caractéristique, conservée dans son état de ruine, rappelle clairement à l’espèce humaine l’impact dévastateur de la guerre nucléaire.

L’un des nombreux aspects fascinants de la société japonaise est qu’elle se perçoit comme étant séculaire et d’ailleurs la majeure partie de sa population se considère athée. On le remarque notamment dans les données démographiques relatives aux affiliations religieuses. Aucune religion n’est particulièrement dominante et les Japonais suivent souvent une combinaison de pratiques issues de plusieurs traditions religieuses. Mais le Japon est-il vraiment laïque ?

Qu’en est-il du Shinto, « la voie des dieux », la foi indigène du peuple japonais ? Les Kami, ou dieux shintoïstes, sont des êtres élémentaires, des esprits sacrés qui prennent la forme de processus naturels tels que la fertilité, mais aussi d’éléments de la nature comme les montagnes, les rivières, les forêts et le vent. Les pratiques, sanctuaires et festivals shintoïstes (matsuri) sont si inextricablement liés à la tradition et aux mœurs sociales japonaises que les gens n’y réfléchissent pas à deux fois et ne les considèrent pas comme étant religieux. Lorsque le bouddhisme est apparu au Japon au 6e siècle de notre ère, il a rapidement coexisté avec les traditions shintoïstes ; plus récemment, au cours de la période Meiji (1868-1912), le shintoïsme est même devenu la religion d’État du Japon. Ce n’est qu’après la capitulation du Japon et la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale que le Shinto et l’État ont été clairement séparés dans la nouvelle constitution.

Nombreux sont ceux qui continuent d’honorer les anciens dieux Shinto en priant sur des autels domestiques ou en visitant des sanctuaires. Après tout, les humains sont censés devenir des kami après leur mort et sont vénérés par leur famille en tant que kami ancestraux. Les sanctuaires proposent des talismans pour tous les aspects de la vie quotidienne, qu’il s’agisse de la santé, de la réussite dans les affaires ou d’un accouchement sans problème.

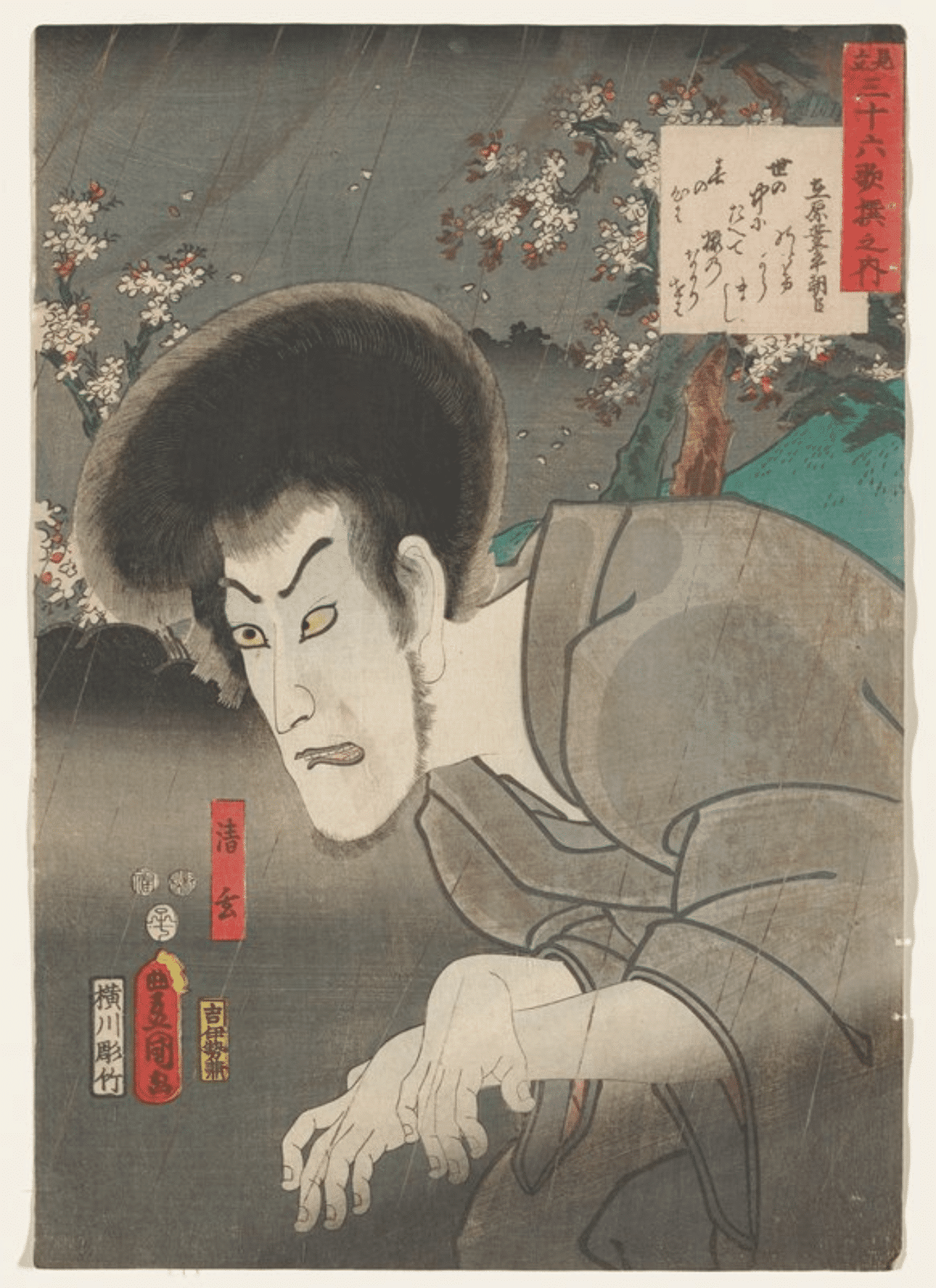

Le Japon n’est donc pas vraiment séculaire. Et, au-delà de ces croyances animistes et rituels de culte des ancêtres, ils ont une place pour l’invisible, l’inexpliqué et ces êtres éthérés qui se cachent dans l’ombre : les yōkai (fantômes, démons ou phénomènes surnaturels) et yūrei, qui inspirent la crainte et le respect dans les moments dangereux ou les espaces liminaux. Il existe une grande variété de ces êtres surnaturels dans la culture japonaise, des plus effrayants aux plus bizarres. Si à l’origine, ces créatures représentaient la peur de l’inconnu ou des maux inexpliqués, ils se sont multipliés à travers la siècles et font vraiment partie de la culture japonaise, que ce soit dans les nombreux festivals qui marquent les diverses saisons de l’année et dans les médias. En raison de leur statut ambigu et de leur nature liminale, ils sont également utilisés pour enseigner aux enfants les valeurs normatives qu’on retrouve dans les contes de fées japonais.

Dans mon dessin, j’ai imaginé comment ces mêmes yōkai qui terrifiaient les marins, voyageurs en forêt, les villageois et les citadins pendant des siècles fuient eux-mêmes avec effroi la puissance dévoyée, contre-nature de l’atome.

Dans d’autres parties du monde, face aux épidémies ou cataclysmes dévastateurs, les gens se tournent vers la religion, qu’ils soient juifs, chrétiens, musulmans, hindous ou boudhistes. Mais la catastrophe ultime s’est produite au Japon, où la religion organisée est pratiquement inexistante. Toute situation a un revers: ici, cette absence d’absolu permit de désigner le vrai coupable : l’homme.

Pour mettre fin à un conflit effroyable, l’homme modifia les germes de la création. Rien ne serait plus jamais comme avant. C’est peut-être parce qu’il n’y a pas au Japon de religion organisée apportant des réponses absolues qu’un véritable mémorial de la paix peut avoir sa place à Hiroshima et être ouvert à tous les hommes, quelles que soient leurs croyances personnelles.