“London in Red”, Alexandre Mitchell, 2025 (59.4 x 84.1 cm, Indian ink)

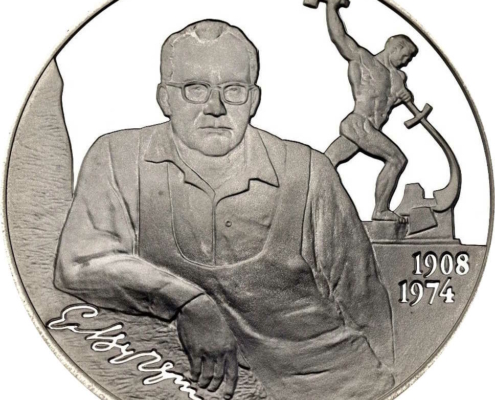

In 1959, at the height of the Cold War, the Soviet Union offered the United Nations a bronze sculpture by Yevgeny Vuchetich entitled “Let Us Beat Swords into Ploughshares”. Inspired by Isaiah’s prophecy of peace (Isaiah 2:4), composed in Judea, c.750-450 BCE. The statue showed a muscular figure hammering steel into a farmer’s blade. To Western democracies, steeped in a Judeo-Christian past, the gesture seemed noble. Yet the choice of sculptor was telling. Vuchetich, more famous for monuments to the Soviet military might —like the iconic 85 meters high The Motherland Calls, built a few years later— was no herald of peace, but an artist of empire. His work, like the biblical image it borrowed, was a gift laced with irony: a Trojan Horse of ideology in bronze. For the Soviet strategy was not only armies and tanks, but the slow work of subversion—changing perceptions, seeding doubt, eroding trust in democracy from within.

In Virgil’s Aeneid (Book 2, v. 48-49), the priest Laocoön warns his people: “Trust not the horse, Trojans. Whatever it be, I fear the Greeks, even when they bear gifts.” Vuchetich’s statue stands likewise as a poisoned gift, a symbol of propaganda cloaked in virtue, its ideology slipping quietly into New York like warriors hidden in wood.

The far left builds its house on vanguardism, for it believes that only a chosen few can lead the masses to freedom; anti-imperialism, which casts the West as the great usurer and extends its hand to any who stand against it; and anti-fascism, which sees fascism less as a creed of hate than as a barricade on the road to revolution. Their dream of uprising may never come, yet they labour in the shadows—printing words, weaving into unions, and hitching their cause to louder movements. Their craft is subtle: they scatter leaflets like seeds of doctrine, slip quietly into student halls, and bend the currents of greater causes—anti-war marches, cries against fascism. Though they wield no bombs themselves—in contrast to Islamists or the far right—, their stories lend a strange shelter to those who do, recasting terror as the echo of foreign wars. How could one forget that the weekly newspaper of the Socialist Workers Party (issue 1960, 16/7/2005) responded to the London transport bombings of 7/7 2005 with the front-page headline ‘This is about Iraq, Mr Blair’. Thus, even without violence of their own, their vision—steeped in workerist zeal and “anti-imperialist” fervor—breathes sympathy for extremism, painting the UK, the US, and Israel as storm clouds blotting out the peace of the world. The Iranian revolution in 1979 marked a first convergence of far-left ideology entwined with Shi’a and Sunni fervour, their voices rising as one chorus against the West. In that crucible, ideology and faith were fused into a weapon of words, a banner of defiance against injustice, oppression, and the gaze of empire. The echoes of that union still resound today, and its cost is one the world continues to bear.

Today this convergence is almost too banal to be mentioned. Fifty years on, the same pattern endures. In the wake of the Hamas massacre of October 7, 2023, vast demonstrations swept London and beyond—rallies less about Palestine than about hatred of a nebulous “Zionist” enemy. Most who marched carried no personal stake in the conflict, only images and slogans shaped by propaganda. Believing themselves to be the virtuous defenders of the oppressed, they replayed a script written decades ago: the radical left’s Manichean vision of coloniser and oppressed, defending the blameless victims of imperialism, a worldview seeded by Soviet subversion and still bearing fruit.

In my painting, I have darkened the face of Vuchetich’s figure and placed his hammer not upon a ploughshare but on a sword smiting the Houses of Parliament—the very heart of British democracy. Below, in contrast, I painted in medieval style King Arthur drawing the sword from the stone: a myth, yes, but one of unity, justice, and national renewal. For Arthur, unlike the Soviet colossus, embodies not ideology but belonging—Britain imagined in stone, in heather, in shared stories passed through centuries.

In 1233, Richard, Earl of Cornwall, exchanged three wealthy manors for the windswept headland of Tintagel, drawn by the legend of Arthur’s conception there according to Geoffrey of Monmouth in his History of the Kings of Britain, 1136. It was an irrational bargain by worldly standards, but a rational one if we remember the power of story. For Arthur was no instrument of Marxist dialectic; he was a symbol of hope, of a people bound by memory and myth.

So I ask: what is Britishness today? Are we not the heirs of countless layers—of hamlets and castles, poems and chronicles—woven into a fabric more enduring than any ideology?

2 Roubles (2008), 100th Birthday of the Sculptor E.V. Vuchetich (28.12.1908) | read more

Cast bronze and granite pedestal, entitled “Let Us Beat Swords Into Ploughshares”, by Evgeniy Vuchetich, donated by the USSR on December 4, 1959. Exterior ground of the United Nations headquarters, New York. | read more